Let’s All Love Max.

Initially, i found Life is Strange to be a sprawling, poorly written, pandering, scattered mess. My take on it will be no better, But i need to write up something soon, before the sequel swallows the franchise into something even further beyond my grasp.

(Edit: I assumed playing Before the Storm would ruin my theory that Rachel Amber didn’t exist. How wrong i was.)

In the year or so since playing, a single scene has really stuck with me; At the party, near the end of Episode 4, a girl is passed out on a couch. Max loudly condemns in her head that ‘no one is helping her!’ Max, of course, doesn’t jump in herself. She just intends to situate herself as pure moral authority; ‘pure’ as in absolute, but also as in extensionless; judgement cast from a void, into a void. Indeed, there is no mechanic offered to help her. She was never really relevant to the hero’s journey.

In the end, we learn the whole town was unimportant. (I only accept Saving Chloe as the True End; and i never really liked Chloe that much. If i could, i would of snubbed both her and Warren to sit around in protestant despair with Kate any day. Anyway.) In the end, Max is just a shell of disembodied criticism, a human mask without interior, clinging to easy values even in the face of immanent oblivion.

The more i thought about it, the more i felt like this was the entire point. I only rejected Max because her character drew me too close to something i didn’t want to confront. So, here’s my scattered, pandering and poorly written reading of a few of the more puzzling and overtly symbolic elements of Life is Strange:

1. The lighthouse is Max

Many were disappointed that you never actually enter the lighthouse. But really, doing so would of made no sense; the lighthouse has no interior.

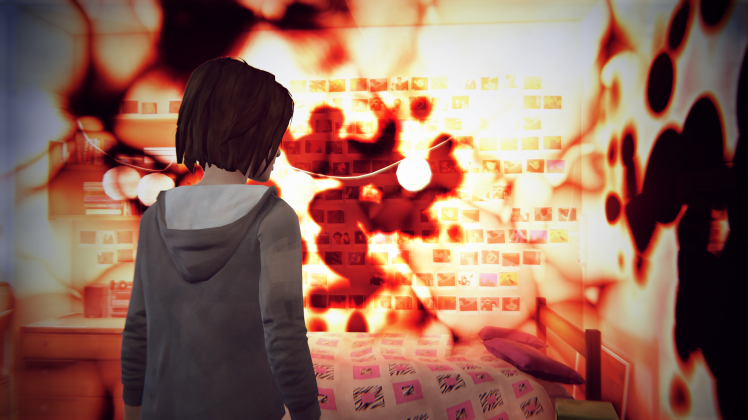

Throughout the game, Max hides her social awkwardness and anxiousness behind the guise of a cool teen identifying as socially awkward and anxious. A selfie: the subject conjuring itself into image. By performing at herself, she escapes the vertigo of interiority. Yes, she is lonely, but a lonely artist, a photographer, a wellspring of feeling, just look at what she captures with her photos. Really, her camera operates precisely as a lighthouse; a lens, projected out onto a world it is not a part of. She uses photography to ossify the world, and to turn away from a dynamic interplay between herself and others, towards herself as curator of an already complete, temporally static, object. And as she says when confronting herself in episode 5, this is exactly how she uses her time manipulation mechanics. There is no temporal grounding between herself and others. A lighthouse guides ships, but stands immobile of the ocean. A photo grants a perspective to a scene the photo cannot coincide with. Max helps Alyssa avoid a puddle, continually readjusts what she says till it is what the person wants to hear, and then fucks off to another world. When she offers advice, it is not as herself, because she no longer exists. In her ‘Everyday Hero’ photo, she stands in the centre of a diaspora of fragments, gazing upon them from nowhere.

2. The storm must be repressed

It’s fair enough Max constantly runs from herself as being present in the world. In their first interaction, we learn that in response to Chloe’s father dying, Max gives up talking to her for several years. Max is shit. She is also thoroughly human. Talking to someone who’s dealt with trauma you haven’t is hard. Communication is the constant terror of being in interplay with positions that escape you, that you can’t comprehend, -that you probably don’t want the burden of actually comprehending,- but still having to provide something to the other with your words. Why not make things easier by subtracting yourself from the equation?

A lighthouse can show a ship what is happening to it, but it can’t intervene. When faced with an insurmountable storm, a lighthouse’s true impotence is revealed. You can gaze death, you can reveal it, but you cannot change it. A photograph always wants to settle becoming into being. A photograph is the denial of the world as tumult, as Boreas, life as weeping flux.

The storm does not only appear at the end of the narrative: We see it pop up as a figureless black spiral circling the dead Bird outside the diner. We see it on the horizon as Max sits on Chloe’s swing set and reminisces about the past. The storm is Max’s inability to mourn what is already lost; Her refusal to see what atemporal existence, being-without-becoming, really is; the abyss of death.

3. Rachel never was.

It makes sense, then, that Max’s ego-ideal is already a corpse. We never meet Rachel. Finding her body bag is just like the moment when the blue box is opened in Mulholland Drive: Rather than finding an interior, the exterior falters against itself. Rachel is Cool, Smart, has perfect grades, but a punk sensibility and a tacky broadway dream. More importantly, she never abandoned Chloe. The hunt for Rachel Amber is precisely the hunt for the ego-ideal: It is Max’s hunt for a version of herself that she could actually accept, a herself she could love qua the world’s love of her. In typical melancholic Max fashion, then, she see’s this as something entirely external; as a living breathing other. Only she isn’t; Max gradual reconciliation with Chloe and her path to self acceptance only comes incrementally through learning Rachel’s spotted past. In the end, Rachel was already dead all along. But really, She wasn’t even that; we never see her body, just a formless black bag. Rachel is a projection, hallucination, already foreclosed in it’s summoning. She is the centre of the storm.

4. Mr Jefferson is Us

One of the moments most jarring and criticized in the game is the opening of act 5: Mr Jefferson is suddenly the villain (no, you did not see it coming, there were no signs, shut up), and not just the villain, -even when Nathan was the villain he had struggles and distinct empathizable character qualities,- no, Mr Jefferson became the conniving mastermind, the bloated action villain; professing his motives and evil scheme in trite soliloquy, the protagonist captive to his violent ruptures and manic controls. Why was a such an out of place kitsch scene immediately preceding the more surreal, deconstructive ending?

Take note of Mr Jefferson’s motives, However. He finds absolute value in the moment of teen crisis, the loss of innocence, the trauma in the coming of age story, and he desires to play through that traumatic moment, again and again, for his emotional pay-off. Mr Jefferson’s motives precisely coincide with the audiences. We’re here, playing this game, to project our suffering onto sprites, to convert our misery into a hyper-sign, and call it art, or at least, entertainment. In these terms, Mr Jefferson’s soliloquy is consistent with the art-cinema-lean of the rest of episode 5; Mr Jefferson’s rupture onto the stage was a highly reflexive moment. The audience coming onto the screen, to kick up a fuss about their pay off not being delivered. (Presented entirely as a big overwrought Fuck You to the actual audience.) Later, while confronting him, one of the dialogue choices for Max is the wholly inconsistent ‘I love you Mr Jefferson,’ forcing upon the audience the role of their mechanics dictating Max, -Max as Bland Pixie Empty Girl,- and making the audience confront the extent their manipulations and Mr Jefferson’s are the same.

But really, Max does love Mr Jefferson, from the start, she admired and wanted to be like him; and, -other than the inversion of Jefferson’s swank sadism and Max’s uncomfortable self-derision,- they embody each other perfectly; they are united in their love for photography; their supreme desire to present the world as a means of escape from it.

5. Arcadia Bay Must Die

Ultimately, we are all Mr Jefferson, and we are all Max. The crisis of the audience and writers are precisely Max’s crisis with her world. A world of escape through repetition and simulation. The storm forces a binary choice upon Max; kill Chloe or kill Arcadia Bay. The audience rightly saw this choice as bullshit; Warren’s butterfly-effect-conservation-of-dimensional-entropy last minute explanation explains nothing, and certainly doesn’t justify why killing Chloe would help anything. But, really, there never was an Arcadia Bay; there was no storm, no time travelling, no mysterious missing girl, no CSI-villain teacher. There’s just Max; an averagely talented artist, and a shit friend, having a well deserved identity crisis, and who conjures a genre-scattered time-travel mystery story to project that confrontation into more heroic disembodied terms. Arcadia Bay was never at stake, as everything was a hallucination from the start. Jefferson is the perverse underbelly of Max’s desire for release, and the storm is the rapturous point of fantasy coinciding with what it necessarily represses; it is the plot revealing the arbitrary and stupid nature of the plot to itself. In the end, there are just a couple of teen girls, standing on the precipice. Chloe and Max; the former locked in rebellious angst over a life not of her choosing, the other locked in the angst of a life of her choosing, to the point it seemed like only existed as a scrapbook of pre-printed, projected images. Even if communication will always fail us, the only thing we can do is have groundless faith in the other anyway, reach out, embrace the hurt, and walk off, into the wreckage of the storm battered world.

Hella.

LikeLike

Go Otters!

LikeLike

Awww I disagree with this so much but it’s really well argued! Opinions!! Argghhh!!! But yeah, this is really well written and interesting and good, made me think about the game in a very different way.

LikeLiked by 1 person